When making a diagnosis of a major depressive episode, it is crucial to take into account any different patterns of symptoms or traits that some people who satisfy the basic criteria for the diagnosis may have because these patterns may have significance for the course of the disease and the best course of therapy. In the DSM−5, these symptoms or feature patterns are referred to as specifiers, and one example of such a specifier is a major depressive episode with melancholy characteristics.

Depression is a mood disorder characterized by depressed mood, loss of interest in or enjoyment of activities, significant weight changes, inability to fall asleep or excessive sleepiness, psychomotor agitation or retardation, exhaustion or loss of energy, excessive guilt or feelings of worthlessness, trouble concentrating, and suicidal ideation and attempts. Some suggest that depletion of monoamines, increased cortisol, and inflammation is linked to depression, although there is yet no conclusive laboratory data to support this.

Melancholia is largely defined by a loss of positive affectivity, which can be seen as either a loss of enjoyment in nearly all activities or a failure to feel better when pleasant events occur. Along with the potential for psychotic symptoms, melancholia also includes abnormalities in psychomotor activity and vegetative symptoms. Psychomotor slowness, an all-pervasive depressive mood, lack of response, and loss of interest are the major characteristics that distinguish melancholic depression from non-melancholic depression. Compared to most other types of depression, this subtype is more relatable and more frequently linked to a history of childhood trauma.

The first outline of the term 'melancholic specifier.'

The melancholic specifier was first explicitly operationalized in the DSM-III. However, it was intended to represent the historical conceptualization of depression that distinguished between milder types of depression, typically considered psychogenic or triggered by a negative experience and depression without an apparent cause. The literature frequently refers to melancholia as a subtype of depression whose onset and biological vulnerabilities strongly influence maintenance.

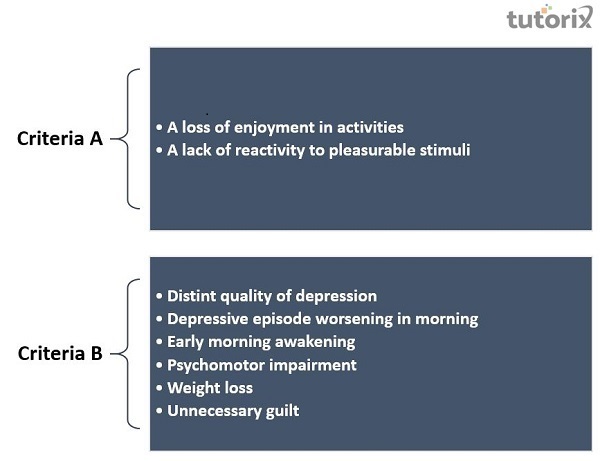

The current episode's most severe phase should coincide with one of the following −

A loss of enjoyment in all or nearly all activities. The capacity for pleasure is almost absent, not just diminished.

Lack of reactivity to stimuli that are often gratifying. Even highly wanted events are not linked to a pronounced mood uplift.

Three (or more) of the following should be present −

A distinct quality of depression marked by a strong sense of hopelessness, despair, and sadness or by a so−called empty mood. A depressed mood that is merely more severe, persistent, or present without cause is not thought to possess distinctive qualities.

Depressive episodes that frequently get worse in the morning.

Early morning awakening (at least two hours before regular waking).

Prominent psychomotor impairment or agitation. Psychomotor alterations are almost always apparent and visible to others.

Profound weight loss or anorexia.

Unnecessary or excessive guilt.

It should be noted that the specifier "with melancholic features" is only used when these features are present, and the depressive episode is at its worst. Melancholic depression is more common among inpatients than outpatients, less likely to occur during milder major depressive episodes than during more severe ones, and more likely to occur in those with psychotic features.

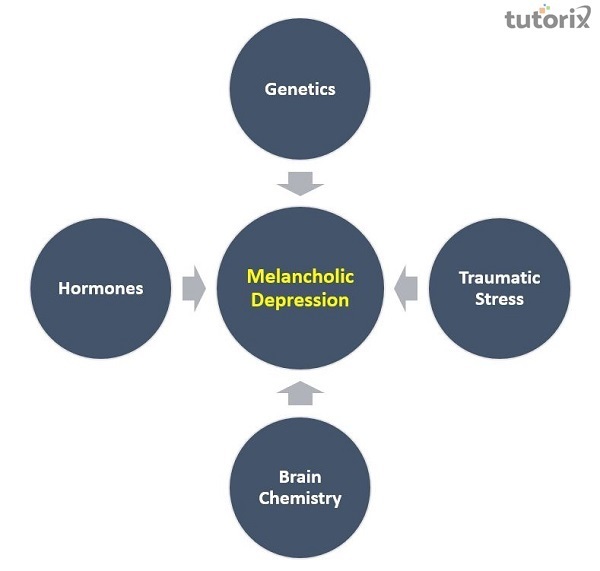

It is unclear what exactly causes melancholic depression, but genetics, family history, prior stress, brain chemistry, and hormones may all be contributory factors. Major depressive disorder with melancholic features is thought to be primarily caused by biological reasons; some people may have inherited the condition from their parents. Stressful events may occasionally bring on an episode of melancholic depression, but this is more of a contributing factor than a necessary or sufficient cause. It is also believed that this illness may be more likely to affect people with psychotic symptoms. Furthermore, it is common in old age and frequently goes unrecognized by some doctors because they think the symptoms are a part of dementia.

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), and lifestyle modifications treat melancholic depression. Melancholic patients are believed to respond better to tricyclic antidepressants (TCA), electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), and other pharmaceutical treatments than SSRIs. When administered by skilled cognitive therapists, CBT is at least as effective as a pharmaceutical treatment. It also appears to have a distinct advantage in preventing relapse, comparable to that acquired by continuing on medications.

The study of mental disorders needs to cease overly depending on medication and concentrate on a more person−centered and humane approach to treatment that emphasizes the patients' actual experiences. Any pharmacological treatment that targets brain disruption is reductive and, over time, may result in some chronic conditions because the breakdown in melancholic depression affects a person in their totality. Successful antidepressant treatment requires an empathetic psychotherapeutic alliance and precise clinical and pharmacological monitoring. Treatments should concentrate on taking negative depression experiences as a whole and aiming for recovery of meaning across the entire spectrum of their lived experience.