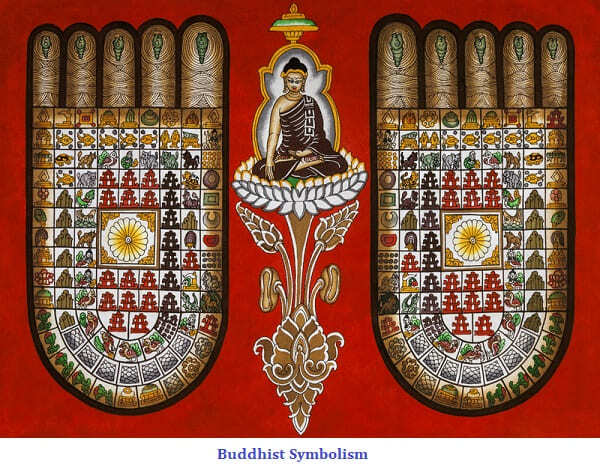

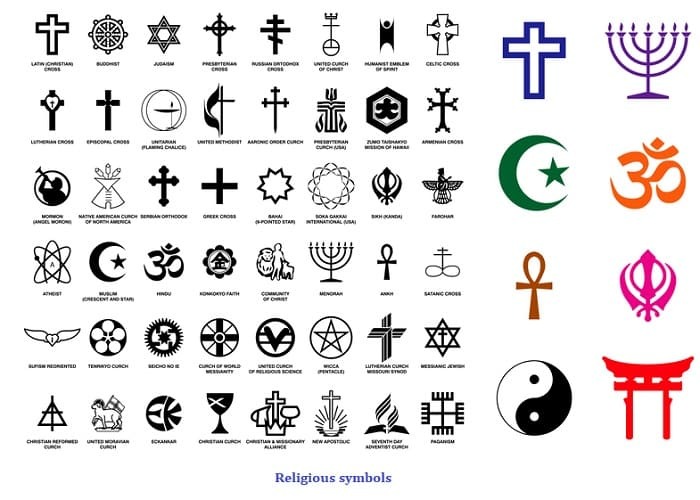

Symbols serve as a medium of verbal communication as well as a means of ritual expression, cultural interpretation, and artistic and religious expression. Symbolism investigates how society works based on the meanings of its symbols, how they are perceived, etc. The interrelationships between individuals, language, and culture are studied through symbolism. Different symbols serve as the building blocks for culture. Symbols can have several distinct meanings. The same symbol may have many interpretations depending on the situation. Symbols follow cultural conventions.

Symbols are signs that are used to denote things, whether they be fictitious or actual. Symbols are chosen at random depending on the cultural norm. Culture affects how a sign is interpreted. Symbolic anthropology aims to answer basic issues about human social existence by examining symbols and the processes—such as myth and ritual—by which people give these symbols significance.

Humans require symbolic "sources of illumination," in the words of Clifford Geertz, to help them navigate the complex web of meaning that makes up any given civilization. Contrarily, Victor Turner claims that symbols are "determinable effects inclining people and organisations to action" and that they "initiate social activity." Turner's perspective exemplifies the symbolic approach, whereas Geertz's displays the interpretative approach to symbolic anthropology.

Imagist poetry gained popularity in the early 20th century thanks to a school of writers who were heavily influenced by Chinese and Japanese poetry. The underlying assumption, in this case, was that language, with its syntax, is inadequate for expression and that tangible pictures themselves work better in poetry than abstract concepts. This was a response to the inversion of pure abstractions. Many poets were affected by this novel idea in poetry. Symbols are utilised in the manner that Clifford Geertz and others have defined them: as systems of meaning that are culturally attributed. When Firth attempted to apply Peirce's definitions to anthropology, he discovered that it was challenging to adhere to Peirce's categorization since in actuality, meanings varied because cultural meanings are contextual and vary as situations do.

The most obvious example of analogic thinking is the purposeful inscriptions on stone from the Acheulian era that resemble drawings and indicate already-emerging creative or artistic abilities. Using art, an artist can communicate thoughts that are present in their head to other members of their organisation. For instance, the prehistoric graphic drawings discovered in caves frequently used only a portion of an animal to depict the entire animal, indicating that the other members of that culture could identify the animal from that portion and that that particular aspect of the animal was valued on a collective level.

Mary Douglas's (1982) studies are based on discovering if symbols are just neutrally expressive or if they have an influence on the social environment, with impacts varying from civilisation to civilization. Ritualism is described as an empty symbol that has no deeper significance and is used by members of society solely as a routine or habit without any other connection to their actions on a deeper level.

Edmund Leach in his 1958 paper "Magical Hair" indulged in melding the ethnographic and psychoanalytical ideas of the body, this has drawn a lot of attention. Leach (1976) has discussed the symbolic meanings of ritual time, including how some yearly rites retain time and enable cosmological calculations of the universe's cyclical motion. According to his theory, time is measured in terms of periods distinguished by symbolic inversions, or reversals from daily life, rather than as a continuous, irreversible linear phenomenon.

Victor Turner performed his research among the Zambian Ndembu people (Africa). Turner investigated how the Ndembu culture had contributed to the tribe's standing by studying Ndembu society. Before and after each hunt, the Ndembu people would honour their ancestors. According to the principle of giving importance to the first tree they come across, they use five different types of trees for worship. One tree had the name Chisinga, which means curse. The Ndembu Chisinga tree is cursed as it represents pace and ladies. While Musoli bore pleasant fruits and when the wind blew, deer were attracted to fruits, and Ndembu hunt these deer thus this was regarded as a godsend.

Although symbolism has never had a distinct core, many people showed interest in deciphering symbolic complexes or patterns to comprehend how society originated. Additionally, symbolic anthropology places the concept of symbols above all other considerations, including human needs, societal change, motivation, desire, etc. Because symbols are abstract, understanding them can be challenging. A symbolic anthropological paradigm like structuralism, functionalism, etc. is challenging to define. Despite opposition, symbolic anthropology has managed to establish itself as a solid and trustworthy theory that is capable of handling the meanings and symbols prevalent across the world's civilisations.

Q1. Who is the founder of symbolic anthropology?

Ans. Symbolic and Interpretive Anthropology began in the 1960s at the University of Chicago, led by Victor Turner, Clifford Geertz, and David Schneider, and is still relevant today.

Q2. Why are anthropologists interested in symbolism?

Ans. Symbolic Anthropology helps to investigate the way people give meaning to the environment or the world and cultural symbols portray this reality in their way.

Q3. What is the central tenet of symbolic interactionism?

Ans. The primary motto around symbolic interactionism is that human behaviour and interaction can be understood by meaningful communication and the interchange of symbols. Humans are acting in this, rather acted upon it.